Construction jobsite death rates have remained stagnant for a decade. Industry mantras have claimed the only acceptable number of injuries and deaths is zero, yet fatalities haven’t budged.

The industry’s fatal injury rate has plateaued at around 10 deaths per 100,000 full-time workers. To help move the needle, safety leaders have begun pursuing new methods to measure success in safety. They say established, existing metrics are flawed.

So, some leading contractors now record and analyze safety data differently. Rather than attempting to negate all jobsite injuries, some have turned their focus to the most severe hazards: the stuff that can kill you.

For example, Paul Levin, senior vice president of health, safety and environmental for Sundt, realized existing methods of measuring success in safety weren’t preventative or accurate enough, even when the contractor successfully reached safety goals.

“That’s what many of us in construction safety think: You do these compliance things, you do these other best practices,” he said. “And it did drive improvement. But when we hit 2019 here at Sundt and we beat our business target of a 0.50 recordable injury rate, our total number of incidents was not going down.”

Paul Levin

Permission granted by Sundt

Levin reasoned that based on construction industry fatality data and Sundt’s work hours of exposure, the company could “expect” a fatality roughly every four years and 61 days. That was unacceptable.

Sundt began trying out a new measurement in 2019 called STCKY, or “Stuff That Can Kill You.” (Sometimes, Levin doesn’t say “stuff,” instead using language more commonly heard on the jobsite.)

Last year, Sundt’s Stop the STCKY program won the Associated General Contractors of America Innovation Award. The program better indicates when workers avoided danger because of direct controls and safeguards or because of luck, so Sundt could act to ensure that those protections were in place more often.

After measuring data, Sundt professionals conduct “STCKY Walks,” Levin said, where they stop work when workers encounter hazards with inadequate protection.

Sundt also educated its workforce and trade partners on their fatal hazards. Its STCKY program emphasizes the Fatal 8 hazards over three categories:

- STCKY Success: No serious injury or fatality with direct controls and safeguards in place.

- STCKY Luck: No serious injury or fatality, direct controls and safeguards not in place.

- STCKY Injury: Serious injury or fatality did occur.

Though compliance for all hazards, regardless of severity, remains key, a new focus on precursors to the most fatal and most dangerous exposures could be a better way not only of measuring success, but also ensuring that workers are better protected from hazards, even when no one gets hurt.

Problems with existing measurements

Construction experts largely agree that current metrics for measuring safety — such as total recordable injury rates — don’t capture how truly safe a jobsite is.

“Someone could close their hand in a door today and that results in stitches, and that’s a recordable incident,” said Phil Clarke, director of safety and risk management for Bakersfield, California-based oil and gas contractor KS Industries. “Another could do the same thing tomorrow and it results in a bruise to the finger.”

Indeed, a 2020 study by the Construction Safety Research Alliance using 17 years of data and 3.2 trillion worker hours discredited the measurement, as it found no discernible association between total recordable injury rates and fatalities.

TRIR is the rate at which a company experiences an OSHA-recordable incident, per 200,000 worker-hours. A recordable incident is a work-related injury that involves loss of consciousness or one that requires medical treatment beyond first aid, days away from work, restricted work or transfer to other work.

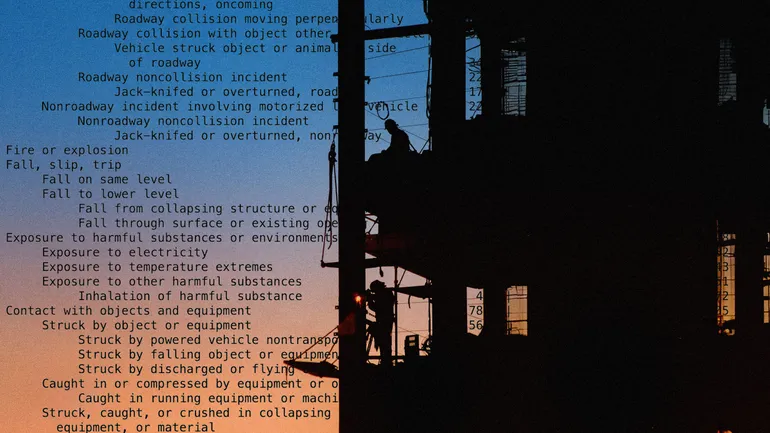

Construction had more deaths than any other industry in 2022

Number of workplace fatalities in the U.S. in 2022, the most recently available data.

TRIR was created and institutionalized by OSHA recordkeeping requirements. For 50 years, TRIR has been used to compare industries, companies and projects, and it is sometimes used as a benchmark of success, CSRA said. Insurance firms also use TRIR to determine worker compensation insurance premiums, CSRA said.

Experts say the flaw with TRIR is in its name: It solely captures recordable events, not the severity of the injury and not near misses.

“A one-stitch cut, a broken leg and a fatality all count the same,” Levin said.

For example, industry leaders have largely gotten away from championing a certain threshold of days without injury.

“When you celebrate such milestones you’re not celebrating a hazard-free workplace, you’re celebrating a recordable injury-free workplace,” said Chris Trahan Cain, executive director of Silver Spring, Maryland-based CPWR — The Center for Construction Research and Training.

Chris Trahan Cain

Permission granted by CPWR

An emphasis on days without injury sometimes leads to masking smaller injuries in what she called “bloody pocket syndrome.” Rather than address a seemingly minor wound, a worker may hide it and address it in their truck or the restroom.

“Nobody wants to be the one who blew the pizza party on Friday, or the truck giveaway next week,” Cain said.

To avoid that problem, safety experts are looking into the recordable and the unrecordable — serious injuries and fatalities and near misses, or SIF potentials.

Stopping the STCKY

Sundt’s Levin wanted to find the situations when workers faced potentially fatal hazards in order to determine how often the appropriate protections — direct controls and safeguards — were in place and how often employees escaped unharmed out of chance.

By looking at recordable incidents and conducting STCKY Walks, Levin found that of 684 incidents in fiscal year 2019, 608 — or 88% — were not likely to result in a SIF.

That meant that, although ensuring adequate protection could still help keep workers healthy and safe, nine out of 10 incidents weren’t as concerning. That narrowed down Levin’s focus.

From there, he looked at the remaining 76 incidents, or 12%, that were more likely to result in a SIF. Four of those times adequate protections were in place, which meant when facing real Stuff That Can Kill You, Sundt workers achieved “STCKY Luck” 94% of the time in 2019.

The stark numbers were alarming, but also provided Sundt with a roadmap. Six years later, having shifted focus and resources, Levin said the team recorded a STCKY success rate of 65% — meaning that about two-thirds of the time when a SIF could have occurred in fiscal year 2024, adequate protections were in place.

That still leaves plenty of room for improvement, Levin knows, as they were still getting lucky about a third of the time. But it’s a far cry from the four times workers were safe from a potential SIF when the process started.

Identifying factors

Bart Wilder, vice president of safety at Birmingham, Alabama-based Hoar Construction, said the company was looking into identifying causal factors for SIFs on the job. It partnered with Richardson, Texas-based insurance company ACIG. Everyday things such as worker fatigue, stress, lack of equipment or falling behind schedule can increase the likelihood of a serious injury, according to ACIG.

Bart Wilder

Permission granted by Hoar Construction

Wilder and his team identified their own causal factors for SIFs, including working in a hurry, not having the right equipment or a schedule change. After about 12 months of research, Wilder said they found the biggest thing that could cause an injury on the job.

“What it showed us was that our biggest challenge had been utility strikes,” he said. “We had done a lot to support our safety program but we were seeing [workers hit utility lines].”

Knowing that excavation work around buried electrical or gas lines proved to have the highest risk of a SIF allowed Hoar to plan in more detail — such as by ensuring they knew the locations of buried utilities ahead of time — to better protect workers, Wilder said. Looking for other precursors and causal factors allowed the company to get more granular with its data.

Simply put, focusing on the most dangerous activities — those likely to lead to a SIF as opposed to a “bloody pocket” injury — allows contractors to be more deliberate with safety planning and prevention.

“It seems very obvious after the fact. There’s every cliche in the industry: Plan your work, work to plan, a failure to plan is planning to fail,” Wilder said.

Clarke said KSI has done something similar. Identifying the most common and most dangerous hazards has led the company to adopt a checklist for its most risky tasks. It gets as specific as an observer checking in via app before, during and after another worker has entered a confined space to do some welding, then doing the same checks before, during and after they exit the confined space.

Learning from a mistake where no one got hurt is a great opportunity to ensure no one is exposed to that mistake again, he said.

“The biggest challenge is getting SIF potentials to realize these are not bad things, they’re actually gifts,” Clarke said.